Beatriz González accentuates the ways printed media contorts, discolors and flattens images. Playing with the idea of error and disfiguration, her colorful silkscreens heighten the imperfections of print, creating flat and cartoonish representations of photographs culled from Colombian tabloids. These four prints follow a similar formula: an image from a newspaper or magazine is enlarged, distorted, colored and placed within a scalloped border, reminiscent of a postage stamp or photographs in a family album. González’s subject matter hints at Colombians’ obsessive consumption of the news, emphasizing the material status of the image over its narrative qualities. The centrality of the figures and lack of compositional depth make them akin to icons.

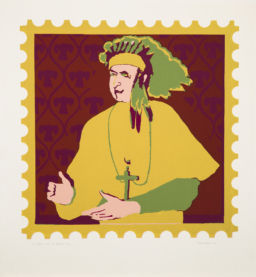

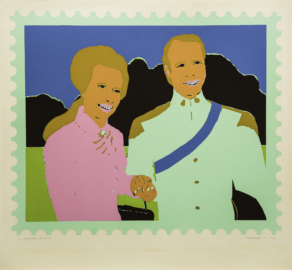

Jackeline Oasis (1975) takes an image from the newspaper El Tiempo and removes the texture and contours that once overlaid her body. Our focus is drawn to the errors in the silkscreen – the thin pink line on the bottom right corner, the bits of orange that overstep their boundary on the camel’s black rump. While the image of Pope Paul VI appears more detailed and his background more ornate in La Iglesia está en Peligro (1976), the disruption of the pattern near his shoulders and face make the composition haphazard. La actualidad illustrada (1973), depicting a rudimentary and ghoulish Princess Anne of Edinburgh with her husband Mark during their trip to Cartagena, nods to Colombians’ fascination with royalty. The two appear cut and pasted atop an amorphous black background, whose thin green outline indicates the presence of shrubbery. The subjects in Lesa Majestad (1974) – Simón Bolívar among them – are particularly warped, as though emphasizing the degrees of separation between the original mural in the Colombian National Capitol building, its photograph in the paper and its reproduction in González’s print.

The imperfections in the silkscreen technique, yielding a lowbrow and parodic print, point to González’s strategic use of what she calls “bad taste.” Her interventions in the image serve as critiques of elite Bogotano sensibilities in the 1970s and stand in opposition to demands on González and other artists to produce work for export, as testaments to Latin American modernity.

Though many associate González’s oeuvre with Pop Art, this connection is coincidental. Her bold palette is inspired by the colors of her childhood church in Bucaramanga, which, at the time, was a provincial town. Her commentaries on mass media are a synchronous but unrelated phenomenon to those influencing American contemporaries Andy Warhol and Rosalyn Drexler. What some might perceive as pop sensibilities in González’s works are, in fact, indicative of folk traditions.

-SS